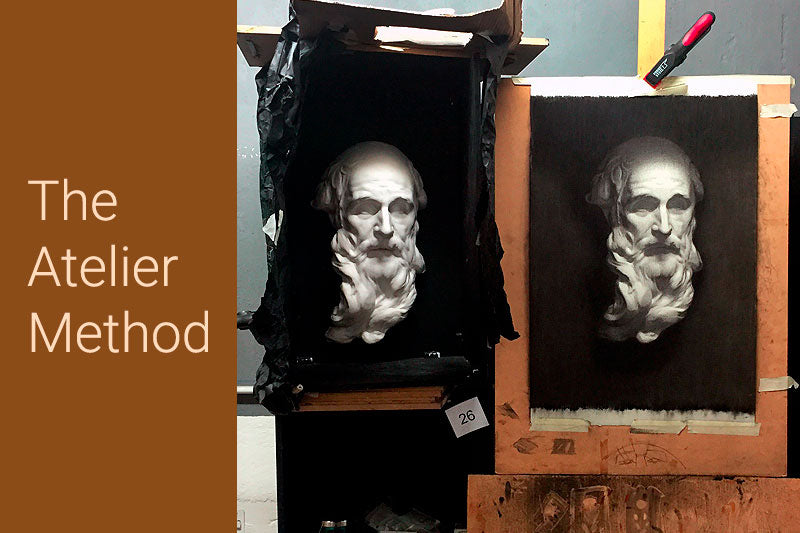

Years ago, I came across life drawing and representational art and found this to be a fun hobby. I went on a quest to become better at drawing, which eventually led me on a path that was enormously enriching; I wanted to be able to draw and paint people. I then learned about the atelier method of training which changed everything. I have been in the training industry for more than a decade and knew some tricks of the trade; but with the atelier training, I was confronted with a training technique that was responsible for some of greatest works of the golden age of painting, about 150 years ago. Somehow this technique was overlooked and forgotten.

Being a training geek I could not stop analysing this world further and the more I examined it, the more I realised how much potential there was in this training method, not just to teach art, but to teach any subject.

In this article, I aim to share my findings with you. You will learn about the atelier method, what it leads to and how it can benefit you today in your own everyday training. The key point is that this method touches on something universal when it comes to teaching and learning that has passed the test of time. The method has been used to teach painting figurative art and portraits, one of the most challenging tasks in art. Somehow, the method seems to have been put aside and buried, even ridiculed, all for the wrong reasons.

The Art of 19th Century or Salon Art

Have you ever visited the national galleries in Europe and marvelled at 19th century European art with near photographic portraits, figures and pleasing compositions? Have you seen a work of art that took your breath away and wondered how the artist managed to capture such an imagined scene so accurately, without the aid of photographs? How did the artist manage to tell a story in a single image, or give you something so aesthetically pleasing that you couldn’t stop staring at it?

Let’s start with the art of the era. Let me show you some of my favourite art works:

Portrait of Édouard and Marie-Louise Pailleron by John Singer Sargent

On The Beach by Eugene de Blaas

La Paye des Moissonneurs by Léon Augustin Lhermitte

A Street Scene Damascus by Gustav Bauernfeind

Caracalla by Lawrence Alma-Tadema

The Death of Wallenstein by Karl von Piloty

A Nubian Guard by Ludwig Deutsch

The Duel After the Masquerade by Jean-Léon Gérôme

These are just a few examples of magnificent paintings. There are thousands more. You may want to look up some of the most skilled 19th century and early 20th century artists listed below. Here, I am focusing mainly on European artists. Each have a body of work that is unrivalled. Many of their works are found in prestigious national galleries around the world, as well as private collections, yet from what I can tell, most people have not heard of many of them. Look up these artists:

- Lawrence Alma-Tadema

- Bouguereau

- Edward Poynter

- Frederic Leighton

- Alexandre Cabanel

- Ernest Normand

- Jean-Léon Gérôme

- Léon-Augustin Lhermitte

- John Singer Sargent

- Anders Zorn

- Gustave Boulanger

- John William Godward

- Gustav Bauernfeind

- Herbert Draper

- Anders Zorn

What is common between the work of all these artists is that their art takes tremendous amount of effort and training. These works are not done in a day. They have been planned and executed to perfection often over long periods of time. These paintings show a certain dedication to the craft and profession of artists that I see is often completely missing from the kind of art you see in contemporary or modern art exhibitions.

Now let’s not get carried away here.

Let’s see what led to such painting skills. You may wonder why this matters if you are here to learn about training. The method used to acquire such skills follows what we have discovered since then. In the past several decades, through neuroscience and computers and cognitive psychology, we understand the brain a lot more. What is fascinating is that the methods used at the time to produce such art, found perhaps by trial and error through the ages, fit very well within the discoveries of the modern science of learning.

I came across the ‘atelier method’ during my artist training days. About a decade ago I become very interested in painting initially mainly as a hobby. Soon I became fascinated with drawing people and portraits. As I got dragged more into this field, I found a world of art that was largely hidden to me, overshadowed and almost buried by contemporary and abstract art of 20th century.

With my new interest I explored this field extensively and found many examples of exquisite and inspiring and yet unknown paintings. I started looking for them in galleries first in London where I lived and then across Europe in France, Italy, Netherlands, Belgium, Germany, Denmark, Spain and others.

I was hooked and eventually decided to enrol in a 2-year full time painting course here in London. Going through the atelier method; I had two primary aims: I wanted to be able to paint like the masters I admired, and second, I wanted to investigate this training methodology. Was there something I could learn from the atelier method that could be applied to train the trainers in my role as a training consultant?

What Art Can Tell Us That Other Fields Cannot

Could I have achieved the same results by enrolling into a modern art course? The answer is no, simply because most art schools or universities do not teach the atelier method at all; in fact, some institutions feel even hostile towards it.

This, I think, is one of the reasons why the method has been less known and unavailable to students. It is always sad when societies dismiss a technique they have already discovered, often through tremendous hard work over decades because of new trends, due to change of fashion, greedy newcomers, politics or even new technologies.

Fortunately, there has been a resurgence in the past couple of decades; new ateliers have been founded in many countries, and there is a rediscovery of this proven technique.

You may now wonder why we need to learn how painting is taught to deepen our understand about learning itself. Let me explain:

The power lies in the difficulty of the task. With the atelier method, the aim is to learn to draw life-like human figure or portrait. This drawing task is by far the most difficult in art, especially when it comes to drawing or painting a convincing life-like face. I don’t even think I need to convince you, just give it a try to draw a face and you would know!

Why Is It So Hard to Draw a Face?

Evolution has programmed us to be very sensitive to faces. We need to able to recognise people—to tell our friends from our foes. We need to pick good genes from bad when searching for a mate to reproduce. We have evolved from social animals and developed body language and facial expressions to read each other emotionally, again leading to extreme sensitivity to the way a face is seen.

Our brains are quick in detecting anomalies, asymmetries and unrealistic features. This is why drawing a face is difficult because you need to get so many things just right.

In contrast, if you draw a tree, however badly, most people will recognise it and may think you did a very good job. But if you chose to draw your mother, don’t expect to get away with even the smallest differences. Those differences will stand out like a sore thumb. No one even has to tell you; you can see for yourself.

This fact was well known to artists in the 19th century which is why they focused so much on teaching figurative art. They believed that once you mastered drawing a face, you could draw anything. The task of drawing a convincing face is challenging, requiring you to develop your eyes and master your medium. Once trained, you could apply your skills to any subject, be it nature, still life or whatever you fancied, and expect to get good results.

When it comes to learning or teaching something, the harder the skill, the more interesting it gets. It becomes a challenge. It is this challenge that can give us an insight into how best we can train people on a difficult topic.

Other than drawing, I consider maths as another skill that is universally difficult. General maths tends to be an essential skill set in life which is why teaching it is so well developed. In contrast, drawing faces is not as critical to learn as maths which is perhaps why a powerful training method such as the atelier method can be overlooked even though it has produced such phenomenal results. It can be argued that the invention of photography might have had something to do with its decline in use, but that is another story.

Drawing figures and faces, because of the way our brain is so sensitive to it, creates a teaching challenge like no other.

This is when a training geek like me comes in and aims to find out how best you can master drawing faces to see what we can learn from the learning activity itself; in other words I was after meta-cognition and here I want to share with you some profound insights.

Does the Atelier Method Work?

To convince you that the method works, all I need to do is to show you my before and after paintings. Let me show you how I was painting faces when I first began painting in my 30s with no prior training. Here is what I produced after my very first short course on oil painting:

BEFORE: Man with a Beard by Ethan Honary - Oil

I am sorry for subjecting you to this. I know, it is not that museum worthy!

As I became more interested, I attended several longer courses, and finally enrolled into a two-year full-time study at the London Atelier of Representational Art (LARA), where I could achieve the following:

AFTER: Costanza by Ethan Honary – Oil

This is the painting of Costanza, cast of a bust made by Italian artist Bernini. The cast is famous in atelier art schools around the world as it is considered a standard cast made available to students going through the programmes. As such, it has become somewhat of an industry standard.

Here is another full figure painting in oil:

Robe by Ethan Honary - Oil

I am sure you agree I have improved by this point. Now, granted, I spent much more time on painting Costanza than the previous one, but it was certainly no easy task. I am using a full palette of colours here even through it looks black and white. I have blue, red, yellow and green there, but all in very subtle amounts. That was the aim of the exercise after all. It is easier to paint a red cloth; it is basically variations of red. However, it is much harder and much more educational to try to capture the warm glow of a neck in a white cast.

I don’t know anyone who has gone through an exercise like this and came out to say that it was easy! When I look back on what I have achieved, I admit that I am pleased with the results; it now hangs on a wall on my living room!

My improvement is down to following a very specific formula that helped me achieve something that I would have considered next to impossible when I first started painting.

It is easy to see this painting and assume the artist is gifted, that I must have had some innate talent to be able to paint this, that it is in my genes, or that as a child I got a lot of encouragement to paint.

None of that is true.

I started painting in my 30s, without any innate talent. You just need to learn the correct technique from a good teacher, practice a lot, allow yourself to make mistakes, get coached, correct your mistakes, and then optimise your overall process. That is all I have done to go from my early days to painting Costanza.

This is what I want to explore in this article with you: You can apply the key principles of the ‘atelier method’ to train your students on any subject. This technique is incredibly powerful. It is easy to apply, doesn’t need some fancy tech as it was used quite well 150 years ago and it delivers results.

I remember Tony Robbins who I admire greatly, once said that, "the cheapest commodity on Earth is advise, anyone can give it to you, and they can be useless or misleading". You need to seek advice from those who get results, because they have achieved what you want to achieve. Their advice will be far more valuable and useful to you.

I want to get the advice of those master artists because when I look at their creations, I can see that they have done what I am hoping to achieve. I don’t need to be convinced by art critiques or salesmen that their work is beautiful. I can see that their masterpieces are not some “random coffee stain on a canvas” as presented in the likes of Frieze Art sold for who knows how much. I just know there is tremendous skill behind them.

That world class skill doesn’t come from nowhere; it comes with impeccable world class training, and it is this training methodology that I am after. I want to know how they have achieved what they have and to discover how to apply similar techniques to teach people how to achieve equally difficult things.

Now, for those who are curious, I paint and draw regularly and exhibit my work in London. You can see my work at www.Honary.com

Here is another example I did in charcoal:

Recorder by Ethan Honary – Charcoal

UPDATE July 2021:

In my new book, Course Design Strategy, I have dedicated a full chapter to the atelier method. I present many lessons in the book on instructional design, drawn from neuroscience, cognitive psychology and the practical art of designing and running courses. The atelier method is a great case study that helps us learn why certain historically established training techniques are so effective. We now have the science to understand why they worked and the insights are quite educational for any modern course design, being instructor-led or online training. Check out my book to learn more about how to design courses that make people learn.

What Is an Atelier?

Now I guess that with that introduction, you must be curious to know how the atelier method works. Let me walk you through it.

In the 19th century, the French art scene was booming, and French artists became the dominant force in art. The French salons attracted large number of visitors, sometimes in excess of 200,000 people. Salons were a place where you could see art, learn about the artists and buy art. The print industry was also emerging at the time which allowed art lovers to buy cheap prints of their favourite paintings.

This increase in art appreciation led to development of many ateliers and academies to keep up with the demand of students interested in learning about art.

Ateliers were run by master artists. Spaces were limited. Ateliers accepted only a small number of students so that the master artist could attend to each student efficiently. Demands for ateliers were high. Their students would go on to art academies to continue with their training.

Some academies such as the Ecole the Beaux Art, one of the most influential art schools in France, had ateliers themselves. Gerome was one of the three professors who ran a sought-after atelier in Ecole. It was considered an honour to be admitted to an atelier such as Gerome’s and so students worked hard to gain drawing skills even before going into an atelier.

How Was Art Taught in the 19th Century?

The aim of the ateliers was to teach students how to paint, ultimately in oil, as it was and still is considered the superior painting medium. But oil painting requires a lot of skill. Instead of throwing students at the tasks, ateliers would set up a roadmap for students to follow. As students became progressively more skilled, they would be allowed to start painting in oil.

The Curriculum

In the atelier method, there was a roadmap of exercises for students to go through. There are several important methods to draw:

Sight-Size

The drawing is done two meters away from the object to capture a similar sized drawing to what is seen. There is a lot of going back and forth to the paper/canvas as you step back to observe and step forward to draw/paint. See “Sight-Size Portraiture” by Nicholas Beer for an explanation of how to draw using this method (Beer 2010).

Comparative Measurement

This is a common technique used in quick life drawing sessions where measurements are made relative to each other. See this video by Alex Tzavaras as he explains how drawing by comparative measurement works.

The atelier method process starts with easy drawing exercises with simpler tools, to more difficult exercises with more complex tools:

- Draw with pencil and copy other pencil-drawn master sketches

- Draw part of a cast with pencil (e.g. an ear or a nose)

- Draw part of a cast with charcoal

- Draw a face cast of medium complexity with charcoal

- Draw a cast of a bust with charcoal

- Paint part of a cast with limited palette in oil

- Paint a medium complexity cast with full palette in oil

- Paint single-object still life with full palette in oil (to get trained on managing colour)

- Paint colourful multi-object still life with full palette in oil

- Paint part of a live model or sketch a figure with limited palette in oil (e.g. half the body, torso, legs)

- Paint part of a live model with full palette in oil

- Paint the full figure of a model with full palette in oil

Additional Exercises

There were also side studies along the way:

- Paint or draw portraits

- Paint or draw master copies from works of master artists

- Paint or draw various still life to learn about composition, colour, object arrangement and light

- Specific small exercises to learn about shadow shapes, terminator, core shadow, colour wheel, secondary and complementary colours

- Quick sketches with short pose life drawing, colour sketching, colour mixing and many other small exercises

Here is an example of what I made using the atelier method at LARA: a cast of St. Benedict by Bernini in charcoal. This was done in sight-size.

My Progress Drawings of the Cast of St. Benedict in Charcoal

The Routine

- 6 Days a week. Students would paint 6 to 8 hours a day for 6 days a week.

- Two feedback sessions. The tutor would see students twice weekly. Gerome famously attended on Wednesdays and Saturdays to give feedback to his students.

- Self-check and feedback from other students. The rest of the time, students received feedback from other senior students while also constantly checking their works against a readily available model.

Entry to the Academy

Having gone through this extensive atelier method, students would then prepare for an entry exam to study at an academy.

The exam was to draw a life model in a set amount of time. In order to prove themselves, the atelier graduates had to share a model with the current students of the academy!

The academy students were required to pass this exam every six months, even though they were already studying at the academy! They had to demonstrate that they were worthy of remaining at the academy.

The new applicants had to draw side by side with the experienced students and perform as best as they could. Consider the pressure both groups felt! The mature students knew if they messed it up, the new applicants would take their places. At the same time, the new applicants were under pressure too as their works were compared to those of more experienced students.

Despite this immense pressure, many hard-working students managed to get in and became the master artists we admire today. Note that I say ‘hard-working’, and not ‘gifted’; being gifted in this system wouldn’t get you far.

This is a fascinating world to study, especially if you appreciate art. To learn more about how the ateliers operated in the 19th century, I highly recommended Albert Boime’s fantastic book on this topic, “Academy and French Painting in the Nineteenth Century” (Boime 1970).

How Does the Modern Atelier Method Work?

Gerome was highly instrumental in setting up his infamous atelier. This was however at a time when the greatest movement in art—modern art—was taking shape. Modern art first came into people’s attention through the works of impressionist artists such as Monet, Cézanne, Renoir and later through Picasso and Matisse. Thus, began a natural decline in the atelier method as art fashion started to change.

Many successful impressionist or modern art advocates such as Sargent and Picasso were themselves accomplished painters trained in the atelier system. In their career, they made a conscious decision to go in a different direction. However, the skills they gained in the atelier system helped them immensely and comes through in their later works.

It is one thing to know how to paint a face properly and then consciously go in a different direction like Picasso does, than not to know how to paint a face at all and then pretend that the half-finished lousy imitation of a face is modern art. You can tell by how little people spend time looking at one of these types of paintings in contemporary exhibitions.

Moving on, despite the decline, the ateliers survived. This was because the students of one atelier, say Gerome’s atelier, would go on to establish their own ateliers and in turn their students would go on to establish some more. After Europeans, Americans became interested and some ateliers were established in the US, especially in Boston. These in turn led to more ateliers and so the chain leads us all the way to the current ones today including famous ateliers such as Charles H. Cecil Studios and Florence Academy of Art in Italy. In London you have London Atelier of Representational Art (LARA), London Fine Art Studios and Barnes Atelier. In the US consider, Mark Carder Studio and Watts Atelier. If you want to find one in your local area, consider looking up the approved ateliers curated by Art Renewal Centre (ARC).

Me Busy Painting a Cast of a Hand at the Atelier

Today we can say there are two general approaches to the method:

The Classical Method

In this method, students start by drawing a simple cast model and progress into drawing more complex casts. At each stage of this process the students need to demonstrate their competency before being allowed to move on to the next stage. Students must redo an exercise if they fail at that exercise. This means that in this environment, each student progresses differently.

Once students have demonstrated their ability to draw inanimate objects, they will move on to life drawing. This includes being in a ‘model room’ where they are positioned based on seniority. For example, in Gerome’s atelier, senior students stayed at the back of a slopping room so they could paint or draw the whole figure while the junior students sit in the front to draw parts of a figure.

In this method, the tutor visits a couple of days a week. This traditional model is not much in use today. The reason is simple.

Cast drawing can be very tedious and students these days don’t want to spend months drawing cast after cast before they can draw a life model. Although this was the norm back then, the world of art has changed a lot since then (as well as the market and our shrinking attention spans). Commercial schools need to consider drop-out rates very seriously.

This is an important point that I will come back to later as it relates to student motivation; something trainers should not ignore.

The Modern Method

The approach used by modern ateliers is that half a day is dedicated to drawing from casts and the other half is dedicated to drawing from a life model. This way, students progress forward by exercising on both tasks.

The catch with this method is that you can overwhelm the students by asking them to draw a life model before they are experienced enough to do so. The life model, unlike an inanimate cast, will move and can get out of position. Unskilled students generally struggle with this.

To avoid making it too challenging or time consuming (remember that drop-out rate again), the courses are designed so that students are always one medium behind when drawing from life than when they are drawing casts. Pencil is easier to draw with than charcoal and in turn easier than oil.

As students master using a medium to draw from casts, they are then allowed to use that medium to draw from life.

The system is designed so that students are exposed to life drawing from the start. This helps to motivate them as casts are somewhat too abstract (although I think they can be quite beautiful when done well).

The advantage of practicing cast drawing is that the model doesn’t move and so it creates a precise ‘undebatable goal’. It makes it easy for the students to see their errors, for the tutor to highlight them and then for the students to correct them. I will come to this again later as it is a crucial part of the atelier method that feeds to the power of its teaching technique; it helps to establish the feedback loop of learning.

In the modern method, you always have at least one tutor a day giving feedback. Obviously, having more than one tutor would be great but that is often considered a luxury. Having said that, the feedback you get may not be more than 10 minutes for the whole day for each piece you are working on, for example, a 10-min feedback for a life drawing in the morning and a 10-min feedback for a cast drawing in the afternoon.

Interestingly, even though the feedback doesn’t sound like much teaching, it is often enough, as there is always a lot more to do and practice than to be told what to do. There is also a readily available model to check against, leading to self-learning and self-coaching.

This is precisely what you want when learning a new skill; the opposite method is that you get lectured a lot and don’t get a chance to apply the lessons; something we see often used in many modern training courses that inevitably fail to lead to any significant long term learning.

What Did the Atelier Method of Teaching Lead To?

Let us pause now and see what the atelier method aims to teach. First, and foremost, the aim is to train the eyes of the students. They need to be able to observe nature and then represent it using a medium. If they understand nature and can capture it accurately, they can then learn to manipulate it based on their creative desires.

While learning representational art, students also learn how to handle a given medium. Again, to master a medium you should ideally have a target. Otherwise it is all too easy to throw a bunch of colours onto a canvas and let your emotions lead you. You will inevitably end up with a colourful mess of an abstract art and convince yourself that it looks pretty.

Observation skills and mastering a medium both require constant deliberate practice which is exactly what the atelier method leads to. These skills are difficult to master.

The reason I am so fascinated with the atelier method of training is because it gives us clues on how to run our training courses to get results.

My 3-Object Still Life Exercise with Full Palette

What Is Great About the Atelier Training Method?

Now that you have been introduced to the atelier technique and see where it fits in the history of art, it is time to switch hats and start looking at it from a training point of view.

We want to analyse this method based on what we know from the fields of educational psychology, neuroscience, and andragogy in the past few decades. We now know a lot more about how adults learn. The question is why the atelier method works. What are the specific components and how can we apply them to other training situations?

You may wonder that all that atelier method does is to get you to practice. However, oeHoyears of simple practice doesn’t necessarily make you an expert. As Anders Ericsson, the world expert on expertise puts it:

“Living in a cave doesn’t make you a geologist. Not all practice makes perfect. You need a particular kind of practice—deliberate practice—to develop expertise.”

Anders Ericsson

So, what makes the atelier method of training unique? Deliberate practice is one, but there is more.

Let me walk you through the features. While going through them, I want you to pause and think how and to what extend each feature is related to your own your training courses.

I am a strong advocate of this example-driven approach of teaching. I am using the atelier method here as an example to explain how key training techniques work. I want you to become familiar with the method and to improve your own courses.

Having explored the features, we will then look to see how to apply these features to our own courses regardless of the topic of training.

Let’s review the features:

Leads to Deliberate Practice

Deliberate practice is a modern phrase coined by Anders Ericsson and popularised by Malcolm Gladwell (Gladwell 2009), though you can easily see it in action in the atelier method some 150 years ago.

Here is how Ericsson describes deliberate practice (Ericsson 2017):

Not all practice makes perfect. You need a particular kind of practice—deliberate practice—to develop expertise. When most people practice, they focus on the things they already know how to do. Deliberate practice is different. It entails considerable, specific, and sustained efforts to do something you can’t do well—or even at all. Research across domains shows that it is only by working at what you can’t do that you turn into the expert you want to become.

Anders Ericsson

The atelier method forces students out of their comfort zone all the time. It is a sustained effort day after day, it is considerable as they go from one exercise or medium to the next demanding one, and it is specific as they need to capture the true likeness of a model. The progression to more complex casts or models while switching to more sophisticated mediums is key in keeping students on their toes throughout the entire programme.

I remember that there was a real limit on how much time I could spend every day on such exercises. This was about 6 hours typically and almost never more than 8 hours. After 8 hours, my brain was exhausted and would shut down, which inevitably led to mistakes creeping up on the drawing, that I would then need to come back to fix the next day. That was deliberate practice in action.

Leads to Constant Practice

There is practicing every day, 6 to 8 hours a day, 5 to 6 days a week. This constant practice allows students to be fully immersed in the activity.

When I was going through the full-time course, I would dream about drawing! My brain was so fully fixated on the topic that I could feel I was progressing amazingly fast just because of immersion. It confirmed the old saying, that:

“You are what you repeatedly do.”

Offers a Well-Defined Goal

There is a clear target. Students need to draw the cast or the model precisely. When they get it wrong, they can usually detect it themselves.

Students can see that something in their drawing is too tall, too narrow, or with a wrong angle. They know that one edge should reach another, and when it doesn’t, they should go back to fix it.

Crucially, they know this without the need of a tutor and constant feedback. This is why having a well-defined model can be instrumental in helping students progress forward even on their own.

This leads to self-coaching as students learn to coach themselves.

Leads to Honest Self-Assessment

Self-assessment can be painful sometimes but since there is a clear objective, there is no disputing poor performance. Students need to find a way to achieve better. Being able to assess themselves constantly, and honestly, helps to accelerate the process of improvement which I consider is a key in the superiority of the atelier method.

Helps Students Develop Observational Skills & Attention to Detail

As the drawing progresses, students reach a point where they can no longer see any difference between their drawings/paintings and the model.

This is when the tutor’s feedback is educational. The tutor can highlight issues and bring them to the attention of a student. This can then lead to an ‘aha moment’, leading to profound insights and learning.

In today’s world, where attention spans are shrinking, an ideal training method must help develop students’ observational skills and attention to detail.

Fits in with What We Know from Cognitive Neuroscience

According to research in cognitive neuroscience we know that in order to learn we need to:

Acquire

- Need to pay attention, follow along, observe and get it.

Memorise

- Need to learn it to remember it. It needs to be associated with what we already know. Memorisation requires repetition through periodic recall.

Apply

- We need to apply it to different situations. In order to apply, the learning needs to be generalised. In no topic, you can train someone for all cases and possibilities. The learner needs to develop a flexible mental representation by applying what they have learned to different situations until the learning is generalised and internalised.

Does the atelier method help with any of these stages? You bet!

It helps all three. Let’s see:

Acquire

- With the atelier method, students need to constantly compare what they have created to a readily available model. There is persistent attention. They need to recognise the differences before the model and their work before they can do something about them. This constant observation and search keep them laser focused on what they need to do and lead them to look for potential solutions.

Memorise

- With the atelier method, students are constantly repeating tasks: shadow shapes, line drawing, measuring, colour mixing, shading, colour matching, brushwork and more. This relentless repetition leads to deep memorisation, almost like muscle memory.

Apply

- While drawing/painting, every few seconds students need to make a decision. They must recall from memory what the correct technique is when handling a problem, what worked before and what didn’t or how other students dealt with a similar issue. They then need to apply a technique, by drawing and painting and then immediately compare the results against a model, and then do it all over again. No two situations are ever the same and so the students are constantly engaged in problem solving. Stage by stage, as the work progresses, they need to apply new techniques suitable for each stage, leading to generalisation and internalisation of the techniques used.

Has a Strong Feedback Loop

Students experience a strong feedback loop which looks like this

They have a goal:

- They aim to capture an accurate representation of a model.

They measure their performance:

- They can measure themselves through direct observation and comparison.

- They can be guided by the tutor on things they have missed because measuring their own performance is also a skill.

They need to change the way they draw/paint to eliminate the differences between their drawing and the model:

- They can do this themselves by trying new methods and approaches.

- They can do this by following the advice of the tutor and other more experienced students.

- They can do this by analysing master works and use them as a model to achieve ideal results.

The feedback loop helps to put students out of their comfort zones, focusing on doing difficult things and leading to deliberate practice.

Encourages Junior Students to Learn from Mature Students

In the atelier method, students from all levels share a life model. They are all in the same room, scrutinising the same model from different angles. Each student uses a medium based on how far they have progressed through the course.

The setup encourages all students to see what others do, provide support, ask questions, share tips and generally learn from each other. Junior students can analyse the work of advanced students and see how they tackled various problems.

Because of this setup, personally, I learned a great deal from other students simply by constantly sharing the same problem with them and asking how they achieved certain results.

You are also encouraged to listen in to tutors as they help other students while you are engaged in your own drawing, which again is educational.

In contrast, consider the modern university system where students of year one study in total isolation from students of year four. It is as if by design this interaction is discouraged!

Pushes Students to Their Limits

While going through the atelier method, I learned a lot because I was pushed hard to become better at ‘seeing’.

While training in the atelier, having worked on a drawing and making a lot of corrections for weeks, I would reach a point thinking that I had done a fantastic job. Other students come to see my work and will praise me for it. By then I was sick of looking at the same piece for so long and felt ready to move on to the next exercise. By the by way, this was a universal feeling and I was not the only student feeling that way. I would feel great. I would think that I was pretty much done with this task and had made a beautiful life-like version of the model.

This feeling lasted until the tough tutor came for a critique! After 30 seconds of looking at my work, he would spot three major issues and 12 smaller mistakes all over the drawing, would dismiss my work as half finished, and tell me that I could now begin to put some details in there! He would imply that the work was nowhere near completion and that I should work harder on it and stop messing around!

Well, that’s what I call being pushed to the limit. I suffered for sure, but when I look back, I can tell that I learned many of the greatest drawing lessons during that last push. As an artist, you need to be able to ‘see’; it is a primary skill. This learning to see can be immensely useful when it comes to composition and craftsmanship.

Now, what is the moral of the story for teaching? The key point here is that in order to learn something complex very well you need to be pushed to the limit. This forces you to do what you ‘cannot do’, as Anders Ericsson beautify expressed. The atelier method in the hands of a good tutor, can deliver that. You may suffer as a student, but you will learn.

Helps Tutors Give Accurate Feedback

Because there is a model, it is clear what students need to do. They must capture a representation of the model using the given medium and technique. It is not based on subjective aesthetics or interpretation. It is not debatable. It is not about fashion or somebody’s opinion, expert or not. It is not about getting praise for efforts.

Either they can capture a true representation of a model, or they cannot.

Because of this, the tutor can give useful feedback. There is nothing to dispute. Once there is a difference between your drawing and the model, the tutor will highlight it and you need to fix it. There could be various techniques to approach the problem which the tutor can explain, but the beauty of representational drawing is that the model stays the same and is used as a reference to teach how to ‘see’ and ‘draw’.

The best analogy to this is learning maths. In maths, there is also a right or wrong answer. It is not debatable. There are a bunch of axioms, some proven theories, along with logic and deductive reasoning to arrive at a conclusion. If you get a step wrong, your solution is no longer valid. You will have to go back and fix it, much like representational drawings. It is not subject to debate or opinion or getting points for being half-right.

Keeps the Craft Separate from the Creative Part

To produce a great piece of art you need both creativity and craftsmanship.

When one of these two elements are missing, which these days is often the craftsmanship, you get the “inverted chair with a missing leg” as art. They claim is that it is creative, which might be, even though it is not necessarily special as I can come up with tens of those with a randomiser. But we can all agree that there is certainly no craftsmanship there; it is just an idea.

To end up with good art you need both creativity and craftsmanship. And with art I mean any creative expression, including, say, designing a high-tech gadget, software or a training course.

The atelier training technique is mainly focused on craftsmanship and for good reason. It is the hardest skill and takes the longest to master. Armed with the craft you can then express yourself creatively until you become better at being creative.

With no craft you cannot express yourself properly, you can be creative in your mind but if you fail to express it, it will not work. Your creative ideas could be good but if you don’t have the means to express them effectively, the external world will dismiss your work.

The craftsmanship is the part that doesn’t need convincing. People can see for themselves. You don’t need an art critique to tell you why the work is well-made. The same goes with product design. A good product speaks for itself, so does a well-designed course.

Helps Tutors Know How They Should Help

Have you ever attended a course where a trainer praises you irrespective of what you are doing? With this approach, beyond getting some praise, mainly for effort, there is nothing to learn from.

This often happens when there is no right or wrong answer and so the tutor cannot provide specific feedback. They fall back to just giving some praise, making sure you are ‘having a good time’ while going through the course.

In certain fields, such as art, when you must judge aesthetics, this is much more prevalent. It becomes subjective.

The atelier method, with its focus on drawing representational art, helps students and tutors to step away from subjective opinions and instead pay attention to facts, which in turn helps with the feedback loop and deliberate practice.

Is Not About Talent

The atelier method proves that even if you are considered “non-arty”, you can still learn to draw very well. You don’t need to have a “gift” for drawing.

Artists are not born, they are made, and the atelier method demonstrates how they are made. It has been argued that this applies to almost all other fields too, short of certain sports where the physical body or genetics can make a difference in performance. Researchers have argued for years that the key to performance is sheer practice, and not some innate talent me or you ought to have.

See “Outliers” by Malcolm Gladwell (Gladwell 2009), and “Talent is Overrated” by Geoff Colvin (Colvin 2019) for a comprehensive exploration of this topic.

Helps Progress at Their Own Pace

With the atelier method, students are focused on their own specific challenges and exercises. Once they can demonstrate their progress, and learned certain key lessons, then are allowed to move on to the next exercise.

This will keep students motivated, because there is always a sense of progression into something more advanced. The new exercises, be it with a new medium or a new model, can immediately feel refreshing and exciting. The method helps to avoid the 4 important issues I identified that hinders motivation.

Each student is pushed to master a task they cannot do well and so must put their utmost effort into. They cannot idle around until some other students catch up. They won’t feel they are slowing down the class. Each student is focused on becoming better every day; the focus is entirely on their own personal progress, with no judgement on when they get there as long as they get there. Just like how you want to do in life, they get to compare themselves only to themselves.

This is unlike many modern courses where scoring higher than the next student in some artificial memory-based exam seems to be the entire goal.

When you learn with the atelier method, you learn for life; the lessons stay with you because all that practicing permanently changes long-lasting neural connections in your brain.

The Atelier Method Helps with The Four Main Areas of Training

The atelier method feeds directly to the four main areas of training that I identify in my Train the Trainer Courses: method, setup, teaching and expression.

Four Areas of Training

Everything you do falls under one of these areas. Let me show you how the atelier training method serves each area:

Method

The atelier method is exercise driven and results driven. It defines a very specific road map and clear goals. The method helps trainers to judge and evaluate students. It makes your job as a trainer much easier since you would know exactly what you need to focus on at any given point for each student as they progress along their individual journeys.

Setup

The atelier training method sets up a strong and unavoidable feedback loop. This makes designing exercises and content much easier as you know where they fit along the feedback loop. For example, would you need to help a student develop better observational skills and ‘see’? Do you have to show them how a given technique is executed, such as mixing colour, or sculpting an area with two brushes?

Teaching

The atelier method suggests that there should be a step by step improvement. The student cannot run before she walks. There should not be frustration or impatience expressed by the trainer if students struggle to learn. The trainer should understand that students fail and learn from their mistakes. The trainer expects them to be challenged and knows they must work hard. There is no spoon feeding by the trainer. There is no cramming, memorisation or gaming an exam by students.

Students need to become skilled and demonstrate those skills through their art, that can be examined and analysed. It is the fairest system and the most rewarding.

Expression

With the atelier method, you become more of a coach, a facilitator of training. You need to know how well to express yourself so that your instructions are understood and can be applied immediately. You are not engaging in an hour-long lecture that is potentially lost. The atelier method makes your job much easier as you focus on ‘transferring’ skills and helping students to ‘gain’ those skills. Your focus will be firmly on your students based on their needs, rather than on yourself and what you need to lecture on.

How to Apply the Atelier Method to Your Own Training

Having explored the features of the atelier method, I now want you to map them to your own training courses.

My aim is to get you into a habit of thinking about the atelier method when you are addressing issues in your own courses. Ask, how can you use the atelier method to address a given problem? Is what you have very different? If so, what needs to change?

Let me walk you through a series of guidelines:

Design the Feedback Loop

Make sure you have the following components in place for any exercise or learning activity.

A clear well-defined objective.

- Let students know what they need to learn and why.

- Let them know what is expected of them.

- Give them an ideal model that they can work towards. The model should challenge them to do something they cannot do already.

A clear performance measure.

- Facilitate a process where students can rate their own performance without needing you to check their work constantly.

A clear action.

- Show them how to correct behaviour to improve their performance and move towards the objective.

Let Students Check Their Own Progress

Rather than constantly relying on you, the tutor, to check their work, you want to devise a system where students can check their own work and correct as necessary. This can be done through a series of self-assessments, based on a well-defined objective or a model.

Not only this helps with observational and analytical skills, it also frees up your time as a tutor which can be spent more efficiently on tailored coaching.

This is a great feature of the atelier method and one that leads to a significant part of its success. It is not necessarily an easy part to design and integrate into a course on a given subject, so you need to think creatively to design such exercises in your own specific field. That is the challenge for you, but a fun one!

Place Students in an Environment of Constant Improvement

Immersion is crucial. An hour of exercise here and there may not be enough. Design exercises that students can engage in day after day while systematically working towards a definitive objective. Much like the atelier method that takes place in a studio, put your students in an environment filled with related tools and props that keeps them excited and immersed in the activity.

Have an Ideal Model Students Can Work Towards

Knowing exactly what is expected of students can be an enormous help. Students know what they need to accomplish to master a skill and you as a tutor know how to provide feedback and score them. There is a sense of progress as students get closer to the goal.

Let’s look at the example again. One of the reasons the atelier training method is superior is the inclusion of a representational model, be it a life model, a cast or still life. The model helps set the tone and the difficulty of the task which is something the tutor can control. The model is never set up to be easy, so a student is always challenged, but it is always clear what the student needs to accomplish, i.e. a representational drawing of the model. Students are therefore clear on what they need to accomplish.

Assign Different Tasks to Different Students

Because you want each student to be constantly challenged and engage in activities they cannot yet do, you cannot give the same task to students at different levels.

However, giving the same task to everyone is much easier which is why it is so commonly used. It leads to what I call, ‘the conveyer-based education system’. This is reminiscent of mass education where each student is treated the same, like a product being built on a conveyor, while going through the ‘education factory’. This way you can only expect poor results.

Customise Task Difficulty Level for Each Student

The aim is to get students exercise things they cannot do. Once they can do the exercise, they need to move to the next challenging exercise. In the new exercise, they again need to be out of comfort zone and forced to improve themselves yet more.

A bit of pressure is good, so is restricting the time it takes to complete a task. Remember the Parkinson Law:

Parkinson Law

“Work expands so as to fill the gap available for its completion.”

If you are not familiar with the Parkinson Law, I highly recommend reading the book, it is hilarious, educational and still very applicable to today’s world (Parkinson 1961).

So, in short, hurry your students a little to keep them focused.

Design the Course with Repetition

Repetition is at the heart of learning. Remember the lessons from cognitive neuroscience: you need to design your courses in a way that helps students acquire, memorise and apply the lessons learned:

- Consider using spaced repetition to maximise learning.

- Use experiential learning to help students practice problem solving.

- Teach by examples and case studies to help students internalise a database of cases they can refer to as they come across problems. This will help develop a generalised pattern of solutions that can be applied to new challenging situations.

Let Senior Students Teach Junior Students

The teaching activity helps senior students to better understand the field they are studying as they are forced to teach someone else. This will also free up your time to focus on other training tasks.

Sometimes, there is an argument that senior students can’t teach well and could potentially hinder the performance of other students. But in practice this is often not the case. Any teaching that senior students do is limited anyway; you are still in charge of the whole training process and the topic priority.

The benefits outweigh potential losses. Consider these benefits:

You can break learning barriers

- A great benefit is that senior students can teach in a different way than you do. This helps breaking learning barriers for those who, for whatever reason, can’t learn from you.

It helps with learning styles

- This also helps with learning styles as students are not subjected to your own specific teaching/learning style and might learn faster if someone else explains the same concept to them.

It helps to create a supportive environment

- You will also create stronger bonds between students, creating a supportive environment rather than letting students form cliques.

Help Students Focus on Actions

Much like in life, actions move us forward. If a student is stuck, think what actions (usually in the form of exercises) can help them out of their current dilemma and to move forward.

Here are some examples:

EXAMPLE 1:

Let’s say I am teaching about capturing light falling on an object and formation of a terminator. I can get a student who is struggling with this to paint an egg under a spotlight. The exercise is the ‘action’ that can help the student reach an ‘aha moment’ and understand the significance of a terminator.

EXAMPLE 2:

As another example, let’s say I am trying to teach my train the trainer delegates the importance of asking questions when training. Without asking questions they could fall into trap of lecturing rather than training. As an action, I ask my students to give a 2—minutes mini demo to the whole class which is recorded on video. They need to explain how something works and do so while asking questions. We can then count the number of questions they ask versus the statements made and they must achieve, say, a minimum of 50% questions to the total of questions plus statements ratio. This is a simple and clear objective to work towards.

Maintain Student Motivation

There should always be a fine balance between pushing and encouraging. Remember, you don’t want your drop-out rate to go up, nor do you want to be responsible for putting a student off a given topic for life.

It means you are telling your students:

“You can go through these exercises at your own pace, I am here to support you. If you are struggling, keep at it until you succeed. Once you do, I will give you the next challenging and interesting task to make sure you are not bored or idling. My aim is to make sure you are challenged, but not overwhelmed.”

Contrast this with giving a group of students the same task, easy for some but challenging for others and then expect them to compete. You could potentially humiliate those who are slow and slow down those who are ahead. In this scenario, it would be easy to push ahead to follow with your own pre-set agenda irrespective of how learners are doing. That is how the drop-out rate goes through the roof, because over time, some think they are not learning anything new while others are overwhelmed by too much content.

Now, just a footnote, competition has its own place and is not discouraged. Competition in a supportive environment is necessary and helpful. Focus on creating that supportive environment first.

An ultra-competitive environment can lead to some terrible experiences. Let me share with you one such story from modern art universities: Students are set to compete with each other to such an extent that a student comes up with a ‘genius’ idea for his final year project: To burn another student’s thesis, in the name of art of course! If you feel shocked, you are not alone. Just imagine how the poor student whose thesis got burnt felt!

We can do better than that…

Let Students Progress on Their Own

You can help students learn at their ideal pace by giving them tailored action-based exercises. Lecturing and expecting students to memorise a bunch of facts would have little effect in long term learning.

To learn, I am afraid, you need to let your students suffer. This suffering should be based on their current skill level. Although you want to let your students learn on their own while going through challenging tasks, you also need to create a supportive learning environment where you can help them move forward when stuck. You also want students to help each other to counteract the suffering.

Final Words

Ultimately, to teach well, help your students go through an unforgettable adventure.

This is precisely what the atelier method does. The suffering, the day-to-day intense concentration, the gradual progress known both to tutors and the students, and the journey students go through together will make the learning experience magical.

If you are wondering, just interview some artist graduates of ateliers and you will see for yourself how passionate they are about the atelier method and what they have learned from it.

There is much to learn from the atelier method; learn it and apply it to your own courses. I will guarantee you that a whole new world will open, making your courses much more effective and your life as a trainer much easier.

References

Beer, N. (2010) “Sight-Size Portraiture”, The Crowood Press Ltd.

Boime, A. (1970) “Academy and French Painting in the Nineteenth Century”, Phaidon Press Ltd.

Colvin, G. (2019) “Talent is Overrated 2nd Edition: What Really Separates World-Class Performers from Everybody Else”, Nicholas Brealey Publishing.

Ericsson, A. (2017) “Peak: How all of us can achieve extraordinary things”, Vintage.

Gladwell, M. (2009) “Outliers: The Story of Success”, Penguin.

Parkinson, C.N. (1961) “Parkinson's law, or the Pursuit of Progress”, J. Murray; reprint edition

About the Author

Dr Ethan Honary is the founder of Skills Converged Ltd. A training consultant, researcher, author and designer with an aim to help trainers worldwide to improve training delivery and course design.

Table of Contents

The Art of 19th Century or Salon Art

What Art Can Tell Us That Other Fields Cannot

Why Is It So Hard to Draw a Face?

How Was Art Taught in the 19th Century?

How Does the Modern Atelier Method Work?

What Did the Atelier Method of Teaching Lead To?

What Is Great About the Atelier Training Method?

The Atelier Method Helps with The Four Main Areas of Training

How to Apply the Atelier Method to Your Own Training

Course Design Strategy

Available as paperback and ebook

Online Train the Trainer Course:

Core Skills

Learn How to Become the Best Trainer in Your Field

Train The Trainer Book

Available as paperback and ebook

Explore Topics

Longform Train the Trainer Guides

All In-Depth Articles

CPD Accredited

Online Train the Trainer Course: Core Skills

Learn How to Become the Best Trainer in Your Field

Full Course Details

How to Reference This Article

Honary, E. (2020) "The Atelier Method Can Significantly Boost Your Training", Skills Converged. Retrieved from: https://www.skillsconverged.com/blogs/train-the-trainer/the-atelier-method

Leave a comment

All comments are moderated before being published.

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.